A network could ‘solve a problem’ or have a function that was beyond the capability of a single molecule and a linear pathway.

In the previous chapters, we discussed how information from the real world is abstracted into vectors and matrices so that machines can learn from it. Methods such as gradient descent and PCA allow us to evaluate how well a model is learning, guiding it to gradually converge toward a “better” behavior, and to reason about how similar different behaviors are.

But similarity always comes with compression. In deciding what should be close and what should be far apart, some information is inevitably smoothed out or discarded. Once we recognize this loss, the question shifts: how do we compensate for what disappears in the process?

What if we change the space instead of the methods?

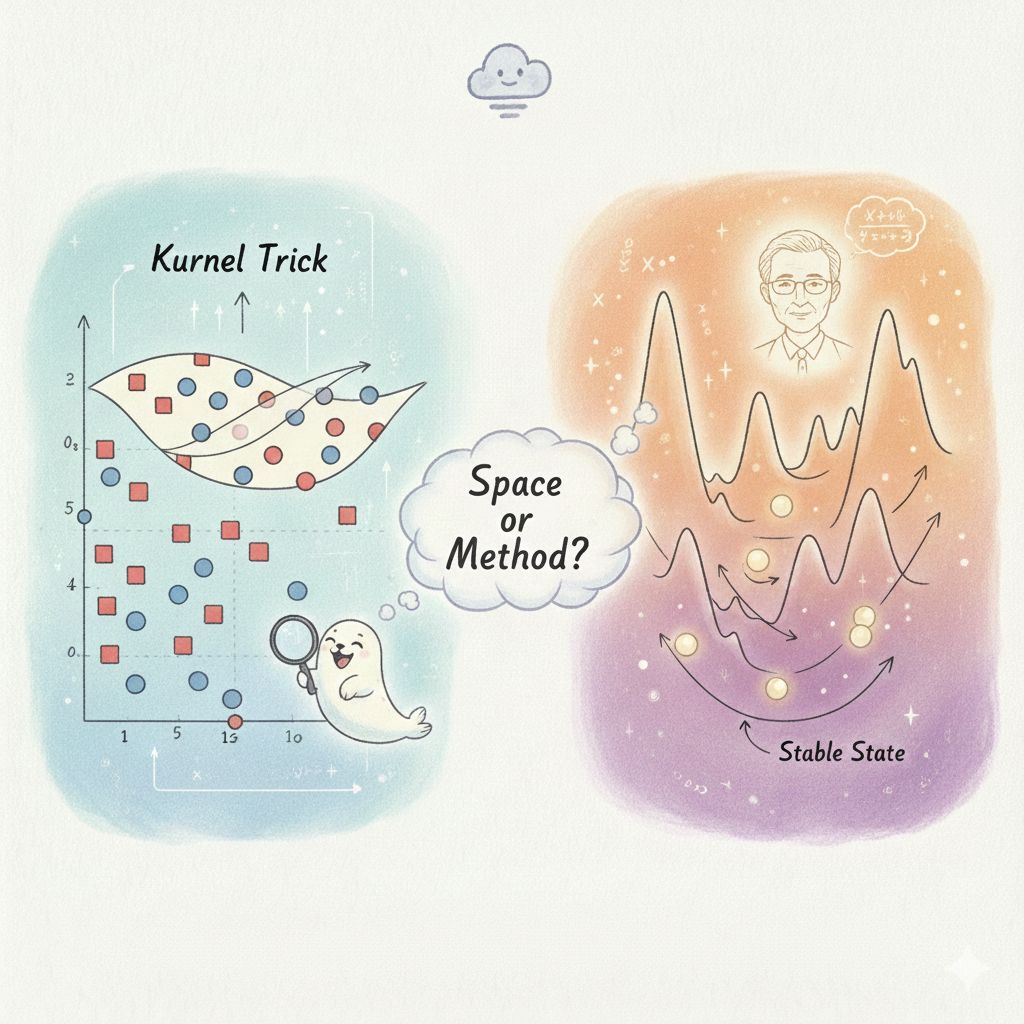

In Chapter 7, the author introduces the kernel trick with a sense of quiet cleverness. In reality, most problems are not linear, which means we cannot simply draw a straight line to separate the data. One way to deal with this is to change the space itself. If we map the data into a higher-dimensional space, points that were inseparable before might suddenly become separable by a single line, or more precisely, by a hyperplane. Thus we can change the nonlinear problem into a linear problem in mathematical way. However, there is a problem that explicitly computing this high-dimensional mapping is often too expensive.

This is where the kernel trick comes in.

Instead of actually lifting the data into a higher dimension, we define a kernel function that directly computes inner products as if the data were already there. More specifically, it is a function that takes two “high-dimension”data points as input and returns a number that represents how similar they are. From the outside, the model still looks like a simple linear one. But behind the scenes, it is operating in a much richer space.

Support Vector Machines are a good example of this way of thinking. Instead of trying to understand the data directly, an SVM looks for a boundary that keeps different points as far apart as possible. With the help of a kernel, this boundary can bend into surprisingly complex shapes in a high-dimensional space, while still relying on a clean and simple rule—much like what we have already seen in linear methods.

The kernel trick feels less like teaching a model to understand complexity, and more like giving it a carefully prepared space where complexity no longer appears.

Can we explain learning with physics?

Chapter 8 brings in physics as a way to think about learning. The author talks about energy landscapes, forces and stable states, and shows how networks like Hopfield nets can be understood as systems that settle into low energy configurations. It makes learning feel like a natural process, almost like a physical law: systems simply roll downhill until they reach a valley.

The author mentioned an important person: Dr.John Hopfield and his ground-breaking research. Interestingly, he did not arrive at his network by starting from machine learning at all. His background was in physics and biology, where he spent years studying systems made of many interacting parts. When these parts were connected into a network. Very different initial conditions could evolve toward the same stable outcome

But to Hopfield, something was missing. There was no language for describing how a large network, taken as a whole, could compute, remember, or decide.

Physics offered him that language. Instead of asking what each neuron should do, he asked how the state of an entire network evolves. Neural activity could be described as a dynamical system, which always tending toward more stable configurations. From this view, computation was no longer a sequence of instructions, but a process of relaxation. The system was not being told what to do; it was simply run follow the natural physical rules.

The Hopfield network emerged from this shift in perspective. Give the system a partial or noisy input, and it would evolve on its own until it reached one of these states.

Personally, I find this both reassuring and a little dangerous.

It reassures me because it gives me a concrete picture to hold on to.

At the same time, it makes it very tempting to treat our models as if they were just obeying nature, rather than executing human designed rules on human chosen data, which is actually what it done.

Closing

Together, Chapters 7 and 8 show how humans design intelligent systems using powerful metaphors. We bend space so that simple rules can appear powerful; we borrow ideas from physics so that abstract optimization feels natural and intuitive. These approaches have pushed the field forward in remarkable ways.

But they also quietly shape how we think about what learning is.

Once learning is framed in the language of geometry and physics, it begins to resemble a process governed by natural law rather than by human choice. The system no longer looks designed; it looks inevitable. In this framing, models are not making decisions—we are led to believe they are simply obeying the structure of the world.

When that happens, bias starts to look like structure, and design choices start to look like necessity.

So when a machine looks at an image and decides what counts as an edge, a face, or an object, we should ask: how much of that “seeing” comes from the data itself, and how much comes from the stories we told ourselves about how learning ought to work?