Newborn ducklings, with the briefest of exposure to sensory stimuli, detect patterns in what they see, form abstract notions of similarity/dissimilarity, and then will recognize those abstractions in stimuli they see later and act upon them.

From here, I’m starting a new series to record what I thought while reading Why Machines Learn: The Elegant Math Behind Modern AI.

It’s a brilliant book that explains the mathematical ideas behind the AI systems we’ve become so “familiar” with in 2025.

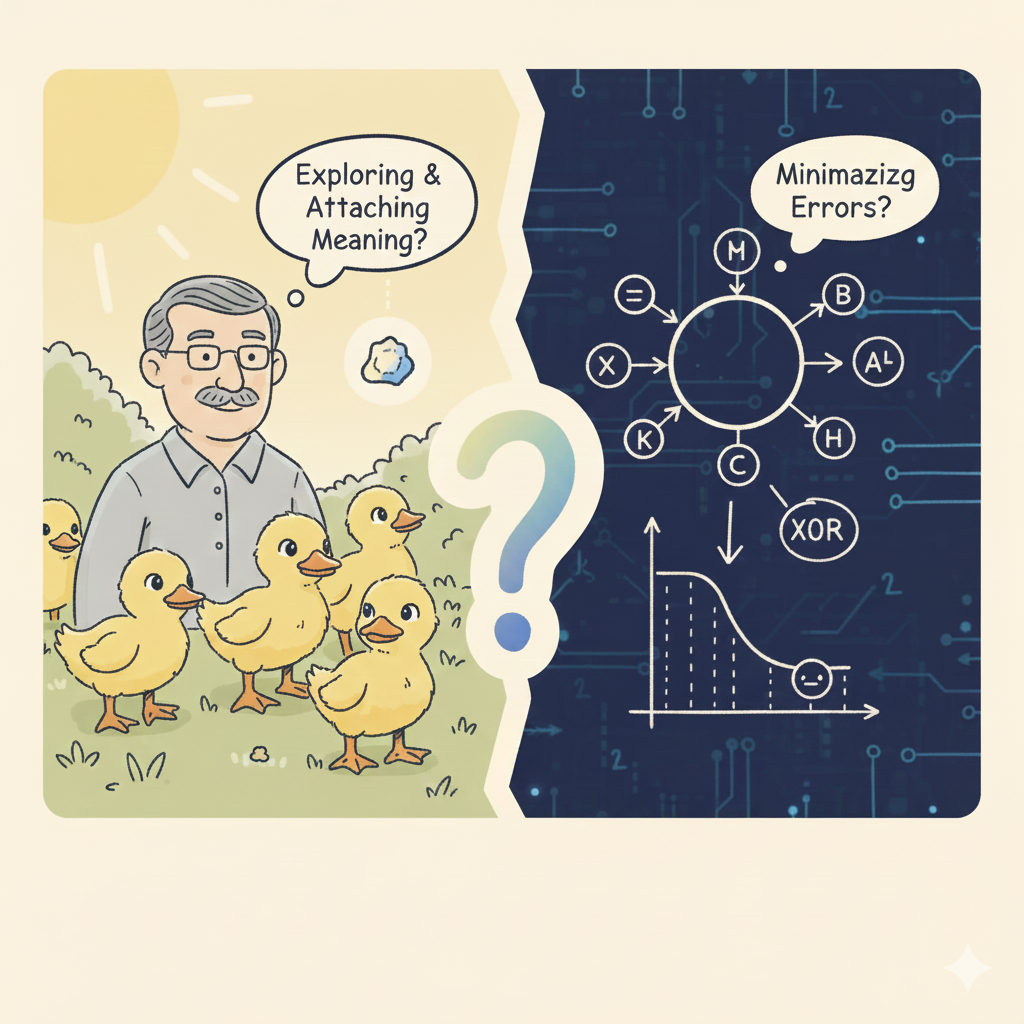

In this first post, I cover Chapters 1 and 2 which begins with ducklings and ends with the simplest version of AI: the perceptron. Somewhere between the duckling and the perceptron, we changed the meaning of learning.

It stopped being about understanding and became about optimization.

The perceptron merely adjusted itself until its mistakes were mathematically minimized instead of understanding. Perhaps that’s what we secretly wish for ourselves too.

What these 2 chapters said?

Our story begins with the scene of Konrad Lorenz and the ducklings, and introduces a very quick, instinctive, and meaningful way of studying: imprinting, which means newborn animals (especially birds, such as ducklings) will identify the first moving object they see as their “mother” and follow it continuously in the first few hours of their lives.

Then people tried to do this in our silicons, and there came the perceptron as the first “learning machine.” After his great explanation, in my perspective it is a simple mathematical model that gives output and reduces error by changing the weights for each input parameter. The perceptron can take multi-dimensional vectors as input and apply linear transformations to them, allowing it to handle many parameters at once. However, a single-layer perceptron cannot solve the XOR problem. Tt’s possible to solve it only if you stack perceptrons, so that the output of one feeds into the input of another.

What do I think of these content?

Notice that from here we changed our way to understand patterns into minimizing the error. The perceptron is just a machine and cannot understand why or what is the logic behind changing the weights.

This makes me think: Is this what we want from intelligence? Perfection, or understanding?

And since a single-layer perceptron cannot even solve the very basic and important problem of XOR, how do we image that it could solve much much more harder task like underatnding reasoning and creating? Think back to the ducklings:

They weren’t calculating or minimizing anything, instead, they were exploring, imitating, and attaching meaning to what they saw.

Their learning came with curiosity and emotion, not with a loss function.

In contrast, the perceptron’s learning is purely mathematical: it adjusts gradients, converges to a minimum, and controls error. Perhaps when countless perceptrons are layered together, something resembling biological analysis and learning begins to emerge. Yet it’s still hard to say whether a machine that learns only by adjusting weights and adding parameters could ever truly approach — or even imitate — the subtle intelligence of a single human neuron.

Closing

In the end, the perceptron did not understand, but it worked. It turned the uncertain and messy process of learning into something that could be measured and controlled.

Numbers moved toward smaller errors, and each correction looked like progress. It abstracted semantics and context into parameters, and then used weights to quantify their attributes/importance. Perhaps that is why its story feels strangely comforting while kind of weird.

It gives us a picture of intelligence without confusion, emotion, or hesitation, only repetition until everything seems stable. Yet intelligence or understanding, whether human or machine, has always been more than stability.

If intelligence is a bowl and we are all sliding toward the bottom, what does it mean to stop?

Does it mean we have already reached the limit of what we can become, or that we are trapped in a loop, unable to find a better answer even when the optimal one might still exist?

Let’s read on and see how the next chapters explore this question.